| III The Sixteenth Century. Historic Song and Chorals | CONTENTS | V The Eighteenth Century. Song and Choir Literature |

{36.} IV

The Seventeenth Century.

Virginal Literature and Church Music

With the seventeenth century there was a deepening of the extreme historical crisis which began in the sixteenth century of Hungarian history. The country, torn into three parts (the Habsburg sphere of interest, the territory under Turkish rule and Transylvania), settled down amid constant warring and internal strife, to a temporary, frontier form of living. There were attempts to regain the lost independence of the Hungarian country, and at the same time there were constant peasant revolts because of the desperate position of the oppressed serfs. The so-called “Kuruc” rising at the end of the seventeenth and the beginning of the eighteenth centuries, and the Thököly and Rákóczi insurrections were a decisive effort towards uniting, under the leadership of the aristocracy, the whole population of the country, including the different nationalities living there. It was an attempt to attain the country’s independence and the liberation of the people, but it was an unsuccessful attempt. The insurrection was suppressed (1711) and the country sank into a semi-colonial state as a result of which the controversies between nationalities and classes became more pronounced. In this critical period musical culture was kept alive at the residences of the aristocracy (mostly in Northern Hungary and Transylvania). For a time they also did a certain amount towards organizing the practice of music among the people.

Tradition of historic song became a sort of silent tradition, disappearing from the surface, to survive in the depths, in popular, scholarly, and also more robust forms, to emerge again from time to time in the market publications of the eighteenth century. The epic literature of the seventeenth century was, however, almost in its entirety meant to be read and not sung, and melody played a very small part. It was the musical conception of lyrical poetry that came into the foreground. This lyrical poetry flourished particularly in aristocratic residences, in castles and manor houses, that at time of the dismemberment of the country {37.} took over the great mission of preserving cultural life. The place of wandering lutenist and vagrant minstrel was taken over by the court musician: the trumpeter and the whistler, who were also used for courier service and who were tower-watchmen and dance-musicians in one person; the virginal player or cembalist whose job it was to cultivate piano music in aristocratic residences, the violin player, about whose play we receive detailed information from the “Ungarische Wahrheitsgeige”, a leaflet published in 1683, – the bagpiper, who also occupied an honoured position in the court of the Prince of Transylvania – the player of the cromorne (or stortist from the Italian name of this double-reed instrument), the trombone player, the cimbalom player, the drummer and others. Residential orchestras were formed and inevitably employed at all house, court and camp festivals. Some of them had a surprisingly big group of musicians. There were for instance 11 Hungarian chief trumpeters at the residence of Ferenc Nádasdy (1648), 9 at the residence of Esterházy (1682), 15 trumpeters served in the household of Imre Thököly (1683), 3 violin players, 1 assistant violinist, 7 trumpeters, 1 lutenist, cimbalom player, whistler, bagpipe player and drummer at the residence of Ádám Batthyány (1658), and 3 trumpeters, 4 trumpeter assistants, 1 Turkish whistler, 1 Polish whistler, 4 whistler assistants, 2 violin players, 1 bagpipe player, virginal player and organist at the court of Ferencz Rákóczi I (1668). The harp player, trombone player and viol player also figure at the residence of the Esterházys in the course of the seventeenth century, while bagpipe, lute, harp, virginal, trumpet and violin were played in the princely court of Transylvania. We even find a Spanish guitar player among the German, Polish, Italian and French court musicians of Gábor Bethlen, Prince of Transylvania. These groups of musicians do not necessarily indicate the actual make-up of the orchestras, but only the musicians available from time to time. However, poems of the period indicate that big and varied ensembles were not rare and that from time to time one or more instruments capable of playing in harmony, were added to violins and to the trumpets (zither, cimbalom, harp, lute, organ and virginal). Not a single note survives of the instrumental music residences, and only a number of trumpet pieces surviving in the Vietórisz Codex, and {38.} Prince Pál Esterházy’s Harmonia Caelestis give us an intimation that the composer must have had direct connection with the practice of orchestral music, Hungarian or foreign.

For the tangible evidence of the instrumental music of the seventeenth century we have to thank the zealous Transylvaniae and Upper Hungarian collectors, who recorded – between 1630 and 1690 – in the form of more or less primitive virginal pieces – folk or “noble” music they came across. János Kájoni* is the most important amongst them; as Franciscan monk and organist in Transylvania, he recorded in the codex called after him a series {39.} of popular dance melodies in organ tablature notation (1634–71); the two unknown notators of the Vietórisz Codex preserved the melodies of 17 love-songs (the so-called “flower songs”) in primitive virginal transcriptions, also in organ tablature notation, and an unknown collector from Lőcse (Samuel Markfelder?), whose series of dance melodies, recorded (likewise in organ tablature notation) in the second half of the seventeenth century, presented the first examples of autonomous, developed virginal music, equally accompished in style, melodic texture and technique of adaptation (around 1660–70). The melodic world, presented in these records, the transcriptions of secular songs and dance melodies, sharply differed from the music of historic song and from the stock of melodies current in the sixteenth century in general.

{40.} Its main characteristics were represented by flexible, finely shaded melodies, a tendency to create wider and looser forms, and a gradual independence of the forma principles of song melodies toward a clearly instrumental conception. The number of rhythms was increased and complicated, rhythmical modifications and rubatos, musical notation became general (Kájoni and Vietórisz Codices), and rich instrumental figurations were taking shape (“choreas” of Lőcse). The manuscript from Lőcse occupies a special place in this literature, because in addition to a relatively accomplished technique it presents an arrangement of dances (“choreas”) according to keys, thus announcing for the first time in old Hungary the cyclic form. It shows not only a conspicuous connection with Polish dance music of the period, but also a remarkable relationship with “verbunkos” music that appears a hundred years later. The virginal book of J. J. Stark in Sopron (around 1689–90) is also worth mentioning. It contains four “Hungarian dances” in a careful transcription (copied by János Wohlmuth, organist in Sopron) among the virginal pieces of international character, recorded in normal notation. And several hand-written collections from the eighteenth century (the Lányi-manuscript from 1729, the Appony-manuscript around 1730, manuscripts from Esztergom and Sepsiszentgyörgy around 1740–50) prove the relatively long existence of the Hungarian dance music style of the period. In addition to the virginal literature of Hungarian character elements of the virginal literature of Hungarian character elements of the Western suite appear at every turn. German, Italian and French dance pieces have their place among the musical repertoire of the residences. The domain, however, where Western inspirations were most directly and richly exploited is to be found in the literature of church music.

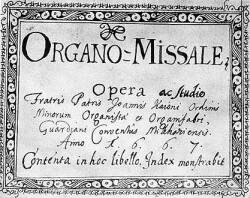

The development of church music in Hungary made a leap forward particularly after the publication of the Cantus Catholici (in 1651; subsequently, as Editio Szelepcsényiana in an enlarged form, in 1675, 1703, 1738 and 1792). In addition to Latin, German and Hussite elements pure Hungarian motives play a significant role in this collection. From here it was only one step to the Hungarian Mass (in the Cantus Catholici of Ferenc Lénárt Szegedi, Bishop of Eger; published in Kassa, 1674), and to the markedly liberal adoption of Calvinist psalm tunes (István Illyés: Soltári Énekek; Psalm {41.} songs, Nagyszombat, 1693), and the introduction of Hungarian choral compositions of generous design (György Náray: Lyra Coelestis, Nagyszombat, 1695). On the other hand the compendium of the Hungarian melodic treasure of the Protestant Church was still not completed, and through Albert Szenczi Molnár’s translation of the Huguenot Psalter (with the relative French melodies, published in several editions since 1607) was even considerably delayed. The first completed Calvinist compendium with the music of the Hungarian melodies was published as late as 1744 and 1751, in Kolozsvár. The Catholic choral literature rose, around the end of the seventeenth century, partly on the basis of Protestant church music, to such heights, that even a new Hungarian church music could spring from it. We find the first notable experiments of this kind in the Organo Missale of János Kájoni (1667, in organ tablature). There are a series of interesting Hungarian compositions {42.} among the litanies of this collection that show remarkable peculiarities both from a melodic and a rhythmical point of view. The stringing together of short motives, syncopated, extended or shortened, result in a complicated rhythmical structure. The unity of the whole, however, is secured through the repetition of motives, in the form of sequences, through the tone by tone repetition or varied repetition of themes. All compositions – in addition to their Hungarian motives – show the strong influence of Italian religious monody, of the works of Viadana, Durante and others. Prince Pál Esterházy’s* compendium, the Harmonia Caelestis, completed around 1700 and published in Vienna in 1711, presents a considerably more developed formal ability and a surprisingly wide use of contemporary techniques. This collection is, to the best of our present knowledge, an unparalleled example of ancient Hungarian music. It is the first and for a long time also the last attempt to create, with the help of contemporary European technique, a Hungarian style in church music. Prince Esterházy was doubtless in close connection with the court in Vienna, opera and oratio literature at its height (Cesti, Bertali, Draghi, Ziani); and also a special “school” of South German musicians (Kerll, Schmeltzer and others) was in the process of formation. Esterházy had obviously studied the new development of the cantata and oratorio style in Venice and Vienna and used what he had learned about form and technique in his short “concertos”. These one-movement compositions (fifty-five in all) were for solo voices, choir and orchestra, with the use of rich and often surprising combinations (violas, violone, harp, bassoon, theorba, violins, flutes, trumpets, organ, timpani). There are orchestral preludes and interludes in some of them (under the name of sonata, and ritornella), and the treatment of instruments in general shows a relatively high technique and a good sense of colouring. The role {43.} of the choir is for the most part limited to homophonic ensembles. Solo voices on the other hand, are given a varied role (Ascendit Deus, Saule, quid me persequeris). Some of these compositions consist of simple, strophic songs (Ave maris stella), others of the alternation of solo voices (canto precinente) and ripieno chorus (Sol recedit igneus, Veni sancte spiritus). Melody and harmony of Viennese, South German and Venetian masters have of course left their marks on these compositions; but their special importance consists in the fact that we can find Hungarian popular motives in many places, and in two pieces (Jesu dulcedo cordium, Cur fles Jesu) even the adaptations of Hungarian chorals. To be sure, this significant lead was only slightly followed by the generation after Esterházy. The ruling musical language in Hungary of the eighteenth century was of German, Austrian and Italian origin, and no special attention was paid in these circles to the seemingly primitive Hungarian melodic treasure.

Indeed after 1700 the Hungarian aristocratic residences betrayed their old traditions and opened their doors to Western music with such a fervour that for about a hundred years they took no notice of the Hungarian music. The Habsburg monarchy, after the liberation of the country from Turkish rule, undertook to “pacify” and colonize Hungary and this imperialistic tendency was meekly supported by the Hungarian aristocracy. The proud Eastern fortresses were turned now into European castles, where the musicians and music of Vienna, Prague, Naples and Milan were eagerly awaited, and modern orchestras in charge of excellent conductors rehearsed new symphonic works and new operas. People no longer had time to listen to primitive music played during dinner time, to “matutinal songs” (hajnal nóta) and simple trumpet or virginal pieces. Together with the outmoded and clumsy ensembles of seventeenth-century residences the Hungarian musical culture of the aristocracy was also disappearing.

Nevertheless this “old Hungarian world” was making a last immense effort about the end of the seventeenth and the beginning of the eighteenth centuries to defend itself. This was the time of the last national uprising. The “Kuruc songs”, born in this belligerent atmosphere, belong to the best part of the Hungarian ancient popular melodic treasure, and were, from the formal point {44.} of view, direct successors of the song literature preserved in transcriptions for virginal, the continuation of the Hungarian Baroque melodic world, probably in a more concise popular version. This in why they have a special historical significance, taking a central position between the style of the ancient and the new folk music. They point to the considerable influence on one another and perhaps to amalgamation that existed at this time among certain elements of Hungarian, Slovak, Rumanian, Ukranian and Polish folk music, caused apparently by the common fight of these peoples for independence. There are almost no contemporary records of them – although the melody of Rákóczi’s song (the patriotic valse associated with the name of Ferenc Rákóczi, the Prince of Transylvania) was already lurking in the Vietórisz Codex (around 1680) and in the so-called Keczer-manuscript (around 1730), and they first made an appearance in bigger numbers a hundred years after the “Kuruc” resurrections, in Ádám Pálóczi Horváth’s Ötödfélszáz Énekek, a hand-written collection of 450 songs, in unclear writing. In view of the extraordinary power of the Hungarian peasantry of preserving old traditions, we believe that Horváth must have heard these melodies in their authentic form from the people, or even from the nobility. Oral tradition, however, modifies text and melody alike in the course of a century, and these modifications cannot be controlled. One or two of them survived almost underground during the eighteenth century, nourishing through their ramified roots a whole line of new popular melodies – until at last around 1780–90 they were first recorded, and at the same time enriched the “verbunkos” literature.

Who was it who endeavoured to make good the neglect of centuries and collected the treasures of bygone times with such care? It seems that a certain historical consciuousness was taking shape among the nameless cultivators of Hungarian music. To understand the essence and forms of appearance of this historical consciousness, we should turn to the scholastic music of the period.

| III The Sixteenth Century. Historic Song and Chorals | CONTENTS | V The Eighteenth Century. Song and Choir Literature |