| II. The Middle Ages. Church Music and Minstrel Music | CONTENTS | IV The Seventeenth Century. Virginal Literature and Church Music |

{24.} III

The Sixteenth Century.

Historic Song and Chorals

“Let us remember”: for it is indeed remembrance that keeps us alive. There could have been no symbol, more timely, of the country torn into three parts, than common resistance, common vital force and common remembrance. It is in this spirit that the song literature of the sixteenth century commences, a literature for the most part recorded, and even printed in the form of {25.} publications with more or less primitive musical notation. In the music printing works in Cracow two Hungarian publications with music were published in the Hungarian language, opening a double line of Hungarian song literature of the period. One is the song book of István Gálszécsi. It is the first Hungarian gradual to the Gregorian hymn-melodies and German choral music of which we can see new Hungarian translations, following in Luther’s footsteps. The other line begins with the Cronica of András Farkas “de introductione Scyttarum in Ungariam et Judaeorum de Aegypto”, the first surviving historic song (a song that records a historical event, a biblical or novelistic subject in a poetic and entertaining form with music). This heads the list of Hungarian epic song literature of the sixteenth century.

Historic songs, as we have seen, are the direct descendants of the historic poems of medieval minstrels but they had to be complemented to some extent, if they were to become the representative type of song of the sixteenth century.* Indeed, the fact that this genre made such a sudden appearance, is evidence of its former existence, even though we have no written records.

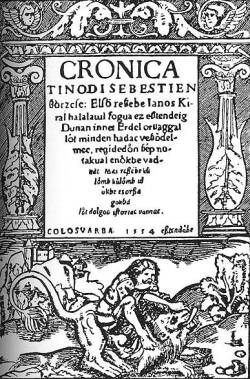

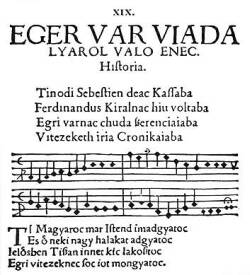

Forty-odd melodies have been preserved. [By naming the tune to which it is to be sung (“ad notam…”) and later prints, we know the tunes of some thirty-five further texts.] This treasure of songs show that we have to deal with music nourished by popular elements and already of specific Hungarian character. It is surprising how ripe was the earliest autochthon music of that Hungarian musical cultural period. This was a period in which foreign elements were absorbed and elaborated in music, and Czech-Hussite, German and Italian types, Latin hymn-forms from the end of the Middle Ages and metrical humanistic odes alike, enriched the wealth of Hungarian forms in the making. The literature of historic song in the course of the sixteenth and at the beginning of the seventeenth centuries brings almost forty types of forms to the surface and these forms are undoubtedly the results of musical shaping in the first place. For the epic poetry of the sixteenth century is in its very essence a song literature, springing from the culture of song and not of written {26.} poetry. The tune was the basis of the composition, the performance and the disseminations of songs, and it played a decisive role in the development, the construction and the creation of the poetry also, while the tune itself, in turn, was changed and modified probably just as much as the tune of folk ballads. It can be said that on the whole the more modern Hungarian rhythmic and melodic textures were already “preformed” in the melodies of historic songs of the sixteenth century. If we examine the melodies of the Hofgreff Collection of bible songs (probably 1553, {28.} Kolozsvár) and particularly Tinódi’s Cronica published in 1554, and if we consider that these melodies, mostly notated in a rigid and clumsy way, were undoubtedly much more colourful and flexible in living performance, we can indeed see little masterpieces of melodic structure and can understand that they were never monotonous even in the repetition of numerous verses. The question arises of how and where such an ability to compose melodies could develop, where do the melodies come from, who created the basis for this music culture with so indivicual a character? Who were these poets and composers?

For the most part they were people with a Latin education – schoolmasters, students, priests, soldiers, wandering lutenists – the Hungarian storm birds of the sixteenth century. We know that some of them also possessed musical education, that in all probability they composed and for the most part performed their melodies themselves. For instance Tinódi,* the most significant musician of the period, who served various feudal lords and travelled all over the country, with the eagerness of a news-gatherer, undoubtedly came across (perhaps in Nagyszombat, Kassa or somewhere else) trends of German Humanist and Czech-Hussite music. His rugged poems are actually turned into poetry by his beautiful melodies – for he wrote, just as all his contemporaries and his successors, with few exceptions, poems conceived in songs, not to be read but to be sung. Through his melodies, Tinódi, this clumsy versifier, turned into the greatest stylist and master of expression of ancient Hungarian epic poetry, from {29.} whose heritage the people’s music of two centuries was unconsciously nourished. We can assume that he, and his contemporaries, possessed a certain rudimental musical grounding, since the singing performance or melody organically belonged, either in the form of recitation or of arioso singing, or of declamation accompanied by lute or fiddle, to historic songs, the moral contemplations and satirical songs. It was as if now there was no longer a Hungarian royal court, the minstrels were scattered all over the residences of nobility, schools, border castles and towns, and as if the former joculator had become schoolmaster or lutenist, student or printer, according to the circumstances under which he found himself. Some brought their musical culture from Italian universities, some returned from the centres of the German Reformation rich with experience and ardent with the desire for reform. Many studied at Cracow, and many encountered in Vienna the renaissance of European spirit. But they all had something in common: they brought with them the excitement of Europe, the intoxication of the age of Protestantism and book printing, and in spite of Turkish wars, religious schisms and world crises they wanted to reach, and did reach, even the poorest huts of Hungary with their ideas.

The Reformation, the invention of printing and the Turkish wars had already stirred up the whole intellectual and social life of the country; but the ties to the Western culture were for a long time still effective. And that goes not only for the music enthusiasts of aristocratic residences, playing the lute, the whistle and later on the virginal, but for the burgesses as well. At that time accentuated declamation, according to ancient practice, of the Horatian odes, and of later religious poems was fashionable at all bigger schools, at the Humanists’ Academies and Protestant communities abroad. The new, rigid choir-singing style is {30.} most significantly represented by the Melopoeiae (1507), a collection made by the Brixen teacher Peter Tritonius (Traybenreiff). A series of melodies, i.e. choir movements, are taken over from this and from other German collections by the school collection of odes of Johannes Honterus, a Saxon reformer in Brassó. This was the first printed work with music in Hungary (1548) and from here – mostly in “accentuated” from – they reached the melodic treasure of the Hungarian Protestant and even Catholic choral. By this means, but with many alterations of course, not only the religious popular songs, but folk songs too, were enriched by some melodic configurations, the presence of which could not be explained otherwise (e.g. the Sapphic verse). Thus we see the approximately simultaneous arrival at this time of the song material of the Czech Reformation, the melodic treasure of the German Reformation and the psalter of French Huguenots. Hungary, and Hungarian music, almost with one stroke, became the meeting place of different European tendencies; Bálint Balassi {31.} (1551–94), the great lyric poet of this period modelled his verse on Italian, German, Turkish and Polish melodic patterns, and studied Regnart’s villanellas. The nobly arched form of the famous Balassi-verse – created actually not by him, but raised by him to the highest form of expression – is begotten by music, born in song and probably inspired by Western tendencies, just as a whole series of Protestant psalm poetry. Other facts speak of connections with Italy. A whole set of Italian musicians was working in the Transylvanian court round about 1590–95. Girolamo Diruta dedicated his Il Transilvano (1593), one of the first manuals of organ and piano teaching, to Zsigmond (Sigismund) Báthory, Prince of Transylvania; and Pietro Busto, a musician from Brescia, wrote a memorandum, containing the description of Transylvania (1595). On the other hand there was the immense stream of folk music, the common property at that time of the whole nation, which absorbed and appropriated all music akin to it, and in consequence a considerable part of historic songs as well. Two melodies of Tinódi have survived up to the present day among the Hungarian peasants. Recently discovered melodies in folk music (from the collections of Kodály in Bukovina and of Lajtha in Transylvania) of Árgirus, a verse-novel from the end of the sixteenth century, as well as of the ballads of Kádár István and Basa Pista, from the middle of the seventeenth century, have probably preserved for us the original tunes to these texts. In the same way a whole series of important pieces of aristocratic poetry in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries were absorbed, together with their melodies, into folk poetry, to be discovered only during recent research by Zoltán Kodály.

The religious popular song was closely connected with historic song. It now became increasingly customary to issue Hungarian graduals. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries the Protestant churches regarded a considerable part of the Gregorian melodic treasure (hymns, antiphons, psalms, responsories, Passions) as their property. This is proved by the Battyhány Gradual (1556–63, a Protestant song-book adapted from a Catholic choir book), Gál Huszár’s Isteni Dicséretek (Praises of God, 1574, containing among others the Hungarian version of Luther’s Ein feste Burg), the Graduals of Nagydobsza, Sárospatak, Csáth, {32.} Óvár, Csurgó, Kecskemét, etc., and above all, the Öreg Gradual (Great Gradual) of János Keserüi Dajka and István Geleji Katona (Gyulafehérvár, 1636). Hence the gradual presents a conservative form. It preserved the melodic world of ancient liturgy and was created only for the use of priests, cantors and choirs. As a more modern form, the common song-book serving the new form of communal singing was gradually coming to the fore. With it the new song poetry was developing, born in the wake of the Reformation, and spreading subsequently to the Catholic church. The number of Presbyterian collections of song texts, made up mostly of free psalm paraphrases, of “lauds”, was increasing since 1560. We meet with their melodies – with a very few exceptions – only later on, in the publications of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries; but the melodies recorded at that time and the tune-indications of sixteenth-century publications equally show a close connection between the melodic material of “lauds” and the melodic treasure of the song literature of historic song. There was as yet no sharp contract made between ecclesiastical and secular, sacred and profane, and severe Protestant pastors angrily reproved those “who sang the holy praise of God in taverns” and who introduced vulgar songs into church singing, preferring the former to the psalms. One of the canons of the Synod of Nagyszombat strictly prohibited the singing in churches of all Hungarian or Latin songs, which had not been definitely approved by their forerunners a hundred years ago or which would not be approved by church authorities of the future, “lest the pious Hungarian people should be led astray under the misapprehension of piety, as may be met with, alas, these days in many places.” The Catholic church recognized the propaganda value of the new songs but at first refused to use them. However, in 1564 the emperor, Ferdinand I, gave the bishops power to permit the singing of popular songs after they had been strictly examined. Within certain limits they also permitted the practice of Hungarian psalms and hymns. Popular songs were again prohibited in 1611 and it was decided only in 1629 at the Synod of Nagyszombat, that a collection of Hungarian church songs be compiled. This plan was realized by the first publication of the Cantus Catholici, arranged by Benedek Szőlősy (Lőcse, 1651, in the {33.} Slovak language ib. 1655). With the appearance of this collection the Catholic church had regained its leading role in the domain of music; the new publication had preceded its Protestant rival by about 90 years in the use of musical notation, and with this collection “musical counter-reformation” gained the upper hand.

In the meantime Hungarian instrumental music was also making an appearance. No Hungarian records are known to us from this period, but ever since 1540 collections of dance tunes abroad included a large number of dances under the heading of “Ungaresca”, “Ungarischer Tantz”, “Passamezzo Ongaro” or “Ballo Ongaro” and other titles, of course in a bold Western stylization in the overwhelming majority of cases. The Hungarian dances of the Heckel (1562), Paix (1583), Jobin, Nörmiger and Picchi collections deserve particular attention. There is no doubt that Hungarian and other East European elements penetrated into the Italian-German melodic world of the seventeenth century, partly from these collections and also partly from other unexplored sources. Almost every “Ungaresca” points to one and the same type of form, to an identical popular dance tune, that even today perhaps could be called, on the basis of sixteenth-seventeenth-century descriptions, the “dance of the heyduck” (guerilla fighter, later foot-soldier in the army of Bocskai in the seventeenth-century war of liberation). We know that this was a wild dance, partly of a shepherd and partly of a military character, accompanied probably by bagpipes, and its music, now mournful now barbaric, could rightly be regarded as an exotic attraction by the fashionable German, Flemish and Italian collectors.

These learned musicians, the compilers of collections, already knew something about Hungary, mainly through the life of Hungarian towns. Many of the border towns of the time jealously preserved their insular German culture and in their seclusion had much more in common with the life of a German town situated some hundred miles to the West, than with that of a Hungarian village vegetating almost next door. These towns soon developed the regular musical life of bourgeois character (the music of tower-watchmen, orchestras), and it is especially significant that, within the framework of their accomplished and {34.} established social structure, they were the first to welcome certain European tendencies and were the breeding grounds of highly talented music inspired by them. Instrumental and choir music flourished here and it does not surprise us that these towns sent envoys to the West who possessed talent of European level. Bálint Bakfark,* the famous Hungarian virtuoso and composer of the lute in the sixteenth century, one of the pioneers of independent instrumental style based on vocal poliphony, received his first musical training in Brassó and in Buda; his phantasies {35.} are among the best of lute literature of the period and account for the prestige they enjoyed among the Polish, German and French public of the time. The famous luteplayers, the brothers Neusiedler began their European career in Pozsony. Stephan Monetarius, author of the threoretical work Epithoma utriusque musices published in 1518 in Cracow, was born in Körmöcbánya. Around the middle of the sixteenth century there was a floruishing musical life in Körmöcbánya, practised by town musicians and tower-watchmen; monumental polyphonic compositions were written in Brassó, Nagyszeben and Bártfa (Anton Jungk 1570, Zacharias Zarevutius 1640), – and this culture, this conscious tradition survived almost to the nineteenth century with undiminished force. In the course of the seventeenth century the following musicians were working: J. Wohlmuth in Sopron, J. Stirbitz and D. Parschitz in Körmöcbánya, G. Reilich and later J. Sartorius in Szeben, D. Croner in Brassó, A. Jungk in Szászorbó, J. Spielenberg in Lőcse, J. G. Seiz in Buda, S. Bockshorn and J. Kusser in Pozsony. J. S. Kusser (1660–1727), Lully’s friend and renowned opera composer, was brought up in Pozsony at the close of the seventeenth century. These centres first took a more direct part in the development of Hungarian musical culture after the end of the eighteenth and the beginning of the nineteenth centries, in other words, after the development of “verbunkos” (recruiting dance) music. At that time musicians and lesser masters of foreign origin and culture: Bengraf in Pest, Berner, Tost, Fusz and Klein in Pozsony, etc., participated in the national musical development of the country. This was the time when the inheritors of Western musical tradition found a place within the framework of a new musical culture of Hungarian character. But before that was possible the whole social and intellectual development of the country had to take a new direction.

| II. The Middle Ages. Church Music and Minstrel Music | CONTENTS | IV The Seventeenth Century. Virginal Literature and Church Music |