| IX Late Romanticism. The Transition Period. Western Reaction at the Turn of the Century | CONTENTS | Hungarian Music since 1945 by György Kroó |

X

New Hungarian Music

This question was actually raised in the first years of the twentieth century by the best representatives of Hungarian culture. As if they had lost confidence in the nation’s way of life in the nineteenth century, in the illusions and art of Romanticism.

At the beginning of the century there was a bright moment in Hungarian spiritual life when it was mature enough to see its possibilities, its startling gaps, and to listen eagerly to the forces seething in its depths. Bourgeois revolution and the social transformation of the country presented themselves as urgent demands. It was inevitable that the reform ideas of the rising new art should extend over the whole life of the nation, as shown by the example of the ancient great Hungarian poetry, the legacy of which was taken {84.} over in the beginning of the century by new music. Their unity was symbolically confirmed by the common announcement of their programme. It was at the same time, in 1905, that the “New Poems” of Endre Ady, the greatest Hungarian poet of the era, were published, and Zoltán Kodály started out in the same year on his first folk-song collecting journey, and Béla Bartók’s first orchestral Suite was performed in the same year for the first time. The three artists who took this path, proclaimed with the same historical competence that the Hungarian people was still “undiscovered”, its energies were waiting to be freed, and that no nation, no creative work and no culture could exist without these energies.

The decisive change came with the emergence of Bartók and Kodály. The creative activity of two exceptional personalities united age-old endeavours to create a Hungarian musical art. This change was in a certain sense nothing but “the return to the main stream” of Hungarian music.

Having left behind Romanticism and the European musical tendencies of the years around 1900, Bartók and Kodály early realized that they must look for their Western masters in the severe and monumental world of ancient, great European music; on Hungarian soil they found the same perfection of tradition in ancient Hungarian folk music. Like a sunken continent or an unknown natural phenomenon, they discovered the oldest and clearest sources of folk music, and in them the hitherto unsuspected ancestral Eurasian inheritance, the oldest and most universal treasure of the Magyar people. They recognized the only organic basis of musical development in the culture of the people. Subsequently they created a varied and universal musical idiom from the material of this popular melodic world, and expressed its contents in various, almost in contradictory ways, but with equal intensity.

Their art was not popular art. It was more than that. It was an individual avowal related to the most profound characteristics of their people, an extensive expression of creative forces. These expressions were, as a matter of course, related to every great historical tradition of the Hungarian people.

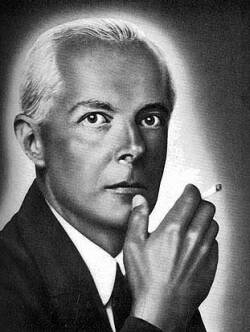

{87.} In his early works Béla Bartók* followed in Liszt’s and Mosonyi’s footsteps, and characteristically he continued, as if unconsciously, Liszt’s almost unknown, late Hungarian creative period (Kossuth Symphony 1903, Rhapsody for piano and orchestra, Two suites for orchestra 1905–7), but he soon abandoned this style and was, for some time, considerably influenced by Strauss’s, Debussy’s and Stravinsky’s art, and became through the dynamic polyphony, bold harmonic and rhythmical reforms of his newer compositions one of the most outstanding leaders of the contemporary innovator movement. (Two portraits 1908, Two pictures 1912, Four pieces for orchestra 1912–21, Dance suite 1923, Bluebeard’s Castle-opera in one act to Béla Balázs’s libretto 1911, first performed in 1918; The Wooden Prince, ballet to Béla Balázs’s libretto 1914–16, première in 1917; The Miraculous Mandarin, to Menyhért Lengyel’s text 1919, premiere in 1926; piano pieces, four string quartets 1908–28, two piano concertos 1926–32). In his works written since 1930 he appears as one of the greatest reformers and synthetists of contemporary European music (Cantata Profana 1930, Music for string instruments, percussion and celesta 1936, Sonata for two pianos and percussion, Violin concerto 1938, “Mikrokosmos” for piano, Divertimento for strings 1939, Concerto for orchestra 1943, 5. and 6. string quartets 1935, 1939, Third piano concerto 1945). This music proclaimed as his aim the union of East European peoples, {88.} the “brotherhood of peoples”. On the one hand it was the revolutionary music of the century with the greatest perspectives. In its extreme contradictions, its logic and its passion, and particularly through the unparalleled tension of its means of expression it showed a way to the whole artistic world. At the same time it reached back to the undiminished energy of ancient folk music, to memories that the Magyars may have brought with them from Asia. Thus it united at the height of revolutionary revival the most ancient with the contemporary.

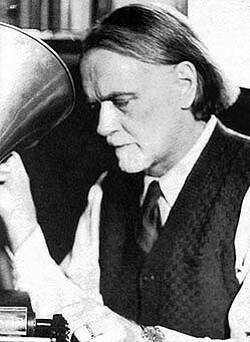

Zoltán Kodály* had already rid himself in his early works of the external, superfluous ornaments of romantic traditions, in order to find the way to an art of classically clear forms and passionate lyric poetry, equally rich in colour and emphasis (Summer Evening for orchestra 1906–1930, Solo Sonata for violoncello, Duo for violin and violoncello, two string quartets, Trio serenade, songs). His path led him straight to the discovery of classical Magyar traditions, of ancient Hungarian poetry, to the revival of great choral forms, to the development of the folk song, to dramatic forms which give sound to the genuine voice of the people for the first time on the stage. In his hands individual and popular melodies are blended together, gradually widening to represent great historical perspectives and becoming the bearers of deepest humanism (Psalmus Hungaricus 1923; Háry János, a musical play to Zsolt Harsányi’s and Béla Paulini’s libretto 1926, The Spinning Room, opera 1932, Te Deum of Budavár 1936, Variations on a Hungarian Folk Song for orchestra 1939, Concerto for orchestra 1940, Dances of Marosszék and Galánta for orchestra, Missa Brevis 1944, Symphony 1961, songs, choral works, folk-song paraphrases, etc.).

{91.} His art occupies a special place in modern music through those characteristic features that connect it with the most peculiar poetic expressions of the Magyar people: the heroic passion of lyric poetry, the Eastern richness of fantasy, yet at the same time the concise and clear discipline of expression, and above all, the rich, flowering melodic world of the human voice, born of the Hungarian language, one of the noblest melodic languages of the time.

The bold plan of Romanticism to raise Hungarian music to the height of universal standards, was realized in Bartók’s and Kodály’s work by the very separation from Romanticism. They reached back to deeper roots to attain a higher artistic perfection. Starting at the same time from ancient folk music and from the principles of Western classical styles, they recreated the Hungarian melodic world, reinstated the laws of the language, the ancient popular modes and popular rhythms. At the same time they opened up unsuspected perspectives in the reform of the harmonic system, by the novel treatment of voice and instrument, and by the profound renewal of the musical language altogether. In this way Hungarian music was raised to world standards. By doing so it gave to Hungarian culture in a certain sense a new content and importance, for Hungary and the world.

The discovery of ancient Hungarian folk song was not only an artistic, but also a scientific achievement. Ever since in 1896 Béla Vikár, with his phonograph, began the collecting of folk songs, a new and most precise scientific methodology became absolutely necessary. Bartók’s and KodáIy’s folk-song publications, the Transylvanian Folk Songs (1923), the Hungarian Folk Song (Bartók, 1924, also in German and English), as well as their historical and comparative essays about folk music (Bartók: Our Folk Music and the Folk Music of the Neighbouring Peoples 1934, Kodály: Hungarian Folk Music 1937, 1943, 1952, in German, English and also in Russian) may, from the point of view of scientific perfection and thoroughness, be included in the front line of European music literature. (Bartók’s work is of fundamental importance also in the field of Rumanian, Slovak, Ukrainian, Bulgarian, Arabian and Turkish folk music). The great comprehensive collection of Hungarian folk songs (Corpus Musicae Popularis Hungaricae), of great international importance, and the crowning {92.} of Bartók’s and Kodály’s scientific activities, began to appear in 1951, under the editorship of Zoltán Kodály.

Just as in the nineteenth century the romantic masters were soon followed by the generation of supporters, adapters and pedagogues, the work of the leaders of new Hungarian music after about 1910 to 1915, and especially after 1925 to 1930, was followed by the activities of the younger generation who made the pioneer work more effective. With the appearance of Bartók and Kodály both the “verbunkos” period, that antiquated, stiffened form of the romantic-national movement, and the tradition of the German academic tendency, lost their vitality. The new movement showed the way to creative artists and to research workers alike. While composers were inspired to increased activity by new works and newly discovered ancient folk-song material, the scientific workers were encouraged by the results of Hungarian folklore, by the collecting of folk songs. The new Hungarian choral movement, the new symphonic, stage, chamber-music and song literature owes its rebirth to Bartók’s and Kodály’s initiative. Their example pointed the way to the generation following in three directions. They discovered and placed Hungarian folk music in the centre of national culture and subsequently developed a monumental new art in the spirit of this folk music; they broke the ground, at a time of national prejudice, for the understanding of tradition and culture of neighbouring peoples: they put Hungarian music at the service of universal progressive ideas. For these reasons their music is a continuous example and an unlimited source of energy.

After Hungary’s liberation in 1945, modern Hungarian musical life was faced with new and serious tasks. Old traditions had to be given a new meaning in the spirit of Hungarian folk music. Socialist Hungarian musical culture had to be built up in the new, free community of the peoples. This was not an easy task, but it can be said that in its essential points the foundation was laid during the past decades. Several factors assisted the development of this rising new art: the inspiration received from the socialist countries, from the institutions that had quickly risen from the ruins of the Second World War, foundation of the League of Hungarian Composers (1949), the Hungarian and international musical competitions, the system of state commissions, prizes and awards, the {93.} growing demands of young people in schools, of people in the factories and the provinces, and in the smallest towns and villages, and above all the serious encouragement from the new music-loving public. The mere existence of such a public, which was continually growing in number, underlined the new social status of the composer, and his connection with the great masses.

The Hungarian people’s democracy has done everything to stimulate and encourage the creative work of composers. Of course, there were certain difficulties in finding the means for new expression but the fact that these difficulties, for the most part, already belong to the past is evidence of the results achieved in the last decades.

The art of Ferenc Szabó, Endre Szervánszky, Pál Kadosa, Ferenc Farkas, Pál Járdányi, Rezső Sugár, György Ránki, András Mihály, János Viski, Gyula Dávid, Rudolf Maros and others is filled by the ideals of service to the people. Ferenc Szabó (born 1902) in his monumental historical triptych (Ludas Matyi, Memento, The Sea Rose Up) united the noble traditions of Hungarian Romanticism with the idea of heroic struggle for a socialist Hungary. Pál Kadosa (born 1903) succeeded in creating a new, individual and varied symphonic language (concertos, symphonies, opera); and Endre Szervánszky (born 1911) expressed the intimate and sensitive beauty of lyrical poetry in his music (orchestral and chamber-music compositions, cantatas, Petőfi-choirs). Ferenc Farkas, György Ránki, Mihály Hajdu, and Zoltán Horusitzky created a stir in the domain of stage music, Pál Járdányi and Rezső Sugár by the revival of the memory of great national heroes in the field of symphonic and choral music. In their work, and that of their best contemporaries, Hungarian music has succeeded in developing a new musical idiom, reflected by different personalities and expressed with different emphasis, but still demonstrating a strong national character. In addition the older generation participates with unabated zeal in the development of modern Hungarian musical culture. László Lajtha (symphonies, stage, choir and chamber music), Lajos Bárdos, Jenő Ádám, György Kósa enrich our reborn musical life with characteristic and individual colours. The younger generation is particularly interested in the problems and experiments of modern European music, and in the {94.} works of György Kurtág, Emil Petrovics, Sándor Szokolay and others this new impulse finds increasing mature expression.

What is the perspective of all these endeavours, all these achievements? We do not know as yet which way they will build up and enrich the coming Hungarian musical culture, what height they will reach, what new colours and energies will emerge in their work. We are certain, however, that the time to come will be the future of a free country that has realized its possibilities, of a strong, varied and special culture of individual character and of great perspectives.

| IX Late Romanticism. The Transition Period. Western Reaction at the Turn of the Century | CONTENTS | Hungarian Music since 1945 by György Kroó |